When you’re raised with a parent in the military, you move around a lot. As a consequence, you don’t really have a hometown.

When you’re raised with a parent in the military, you move around a lot. As a consequence, you don’t really have a hometown.

Until college, The Kid lived in the same house and had the same bedroom since birth.

By the time I’d moved out of my parents’ home when I married, I’d lived in ten different houses in five different cities. Military brats get to choose their own hometown. It might be where we were born. Or maybe the hometown of our parents, normally visited enough to instill both history and familiarity. For some kids, it’s the place we were living when our parent retired from the military. Others choose the town where they lived the longest, or went to college, or vacationed as a child.

Military brats get to choose their own hometown. It might be where we were born. Or maybe the hometown of our parents, normally visited enough to instill both history and familiarity. For some kids, it’s the place we were living when our parent retired from the military. Others choose the town where they lived the longest, or went to college, or vacationed as a child.

I chose the place I fell in love. Or rather, I chose the place I fell in love with.

Or rather, I chose the place I fell in love with.

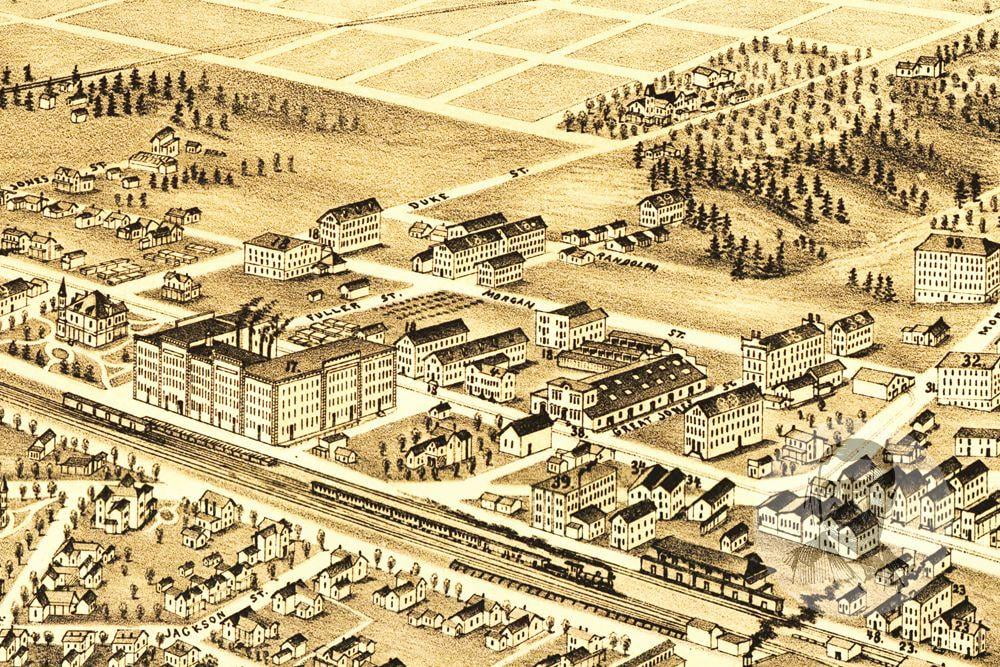

In 1986 Petey and I were living in Elizabeth City. We’d been married three years, and I had an opportunity to move to the heart of Carolina for a job promotion. I wanted to come, Duke hired my awesome husband, so we pulled up stakes and moved.

Nationally, the economy was stagnant. Locally, things were worse. A huge, historic industry was undergoing massive changes which translated into widespread plant closures and exploding unemployment. Always more lunchbox than three martini lunch, the small city suffered mightily. Stores and homes went vacant, became boarded up, and fell into decline. Crime went up, and its reputation, already less than glamorous, plummeted.

Always more lunchbox than three martini lunch, the small city suffered mightily. Stores and homes went vacant, became boarded up, and fell into decline. Crime went up, and its reputation, already less than glamorous, plummeted.

But just because everybody from away was writing eulogies, and reading epitaphs, didn’t mean my fellow residents and I were wearing black and picking out coffins. The heartbeat of this town is the rhythm of people from all different races, classes, religions, and philosophies. Living together, working together, and getting along together. It wasn’t all Kumbaya all the time, there were disagreements, controversies, and tragedy.

The heartbeat of this town is the rhythm of people from all different races, classes, religions, and philosophies. Living together, working together, and getting along together. It wasn’t all Kumbaya all the time, there were disagreements, controversies, and tragedy.But through it all, the citizens of this town kept talking. Sure, sometimes it was a shout, and sometimes it was through gritted teeth, but there was conversation. And there was laughter and tears, but they were shared, which magnified one, and minimized the other.

Then something happened.

Then something happened.

The residents voted in leadership that was passionate about turning the little burg around. Unlike some politicians, they weren’t in it to amass power and shore up their bank accounts. Not everything they did worked, and not everything they did made all of the residents happy.

And it took time.  But, thirty-two years after we made the move, my hometown is one of the coolest, friendliest, most diverse, and economically viable cities in the South. My quirky little metropolis has won awards and accolades from all over the world. But it still keeps that bohemian, working class, wealthy retired, soccer mom, hipster, hi-tech, low-pretension vibe that made me fall in love all those years ago.

But, thirty-two years after we made the move, my hometown is one of the coolest, friendliest, most diverse, and economically viable cities in the South. My quirky little metropolis has won awards and accolades from all over the world. But it still keeps that bohemian, working class, wealthy retired, soccer mom, hipster, hi-tech, low-pretension vibe that made me fall in love all those years ago. The other night I walked out of a funky new restaurant into a bustling, revitalized downtown. The strains of a solitary saxophone floated through the streets like an incandescent ribbon. I was so proud of my hometown, I almost cried.

The other night I walked out of a funky new restaurant into a bustling, revitalized downtown. The strains of a solitary saxophone floated through the streets like an incandescent ribbon. I was so proud of my hometown, I almost cried.

And of course, life means change. Right now, there is real concern that gentrification is altering the balance of the have-a-lots, and the haves-not-so-much. Real estate has skyrocketed, and both taxes and the cost of living is going up. It’s the very definition of, “Be careful what you wish for.”

It’s the very definition of, “Be careful what you wish for.”

But my hometown still has the collective wisdom to choose thoughtful, compassionate leaders who understand and deeply believe that a public servant should actually serve the public.

We should all be so lucky. Thanks for your time.

Thanks for your time.

I answered the phone, dealt with out-patients coming in for testing, alerted staff to emergency orders, and carried in-patients’ results to the appropriate floor.

I answered the phone, dealt with out-patients coming in for testing, alerted staff to emergency orders, and carried in-patients’ results to the appropriate floor. My biggest stumbling block when I started was the lexicon. When I was a newbie and answered the phone, what I heard on the other side honestly sounded like a foreign language. I recognized the articles, and a few verbs, but everything else was totally incomprehensible. When I had to place a call, the message had to be written down, word for word, phonetically.

My biggest stumbling block when I started was the lexicon. When I was a newbie and answered the phone, what I heard on the other side honestly sounded like a foreign language. I recognized the articles, and a few verbs, but everything else was totally incomprehensible. When I had to place a call, the message had to be written down, word for word, phonetically. One is to define the terms that are particular to the group. If you’re a baker, you don’t need a vocabulary for types of blood cells. And if you’re a lawyer, you don’t have a lot of call for the names of different parts of a shoe. That’s the main reason.

One is to define the terms that are particular to the group. If you’re a baker, you don’t need a vocabulary for types of blood cells. And if you’re a lawyer, you don’t have a lot of call for the names of different parts of a shoe. That’s the main reason. The other reason is a snapshot of human nature. It’s done to create an exclusivity. So that outsiders are immediately pegged as outsiders. It’s a verbal secret handshake.

The other reason is a snapshot of human nature. It’s done to create an exclusivity. So that outsiders are immediately pegged as outsiders. It’s a verbal secret handshake.

From Michigan, I learned the language of stillness. As a toddler I would sit quietly every afternoon and a fawn which had become a friend would approach me, every day venturing a little closer for a silent chat.

From Michigan, I learned the language of stillness. As a toddler I would sit quietly every afternoon and a fawn which had become a friend would approach me, every day venturing a little closer for a silent chat. When the Normans conquered the Anglo Saxons, they brought martial words of conquest like jail (spelled gaol in England), armor, and battle. Once the occupation began in earnest new words like tax, rent, and state.

When the Normans conquered the Anglo Saxons, they brought martial words of conquest like jail (spelled gaol in England), armor, and battle. Once the occupation began in earnest new words like tax, rent, and state. When the new nation of America expanded, they discovered the patois of life in the west, mainly from the Spanish who had already been there for couple hundred years. Words such as lariat, vista (not the Bill gates kind), pinto, and buckaroo.

When the new nation of America expanded, they discovered the patois of life in the west, mainly from the Spanish who had already been there for couple hundred years. Words such as lariat, vista (not the Bill gates kind), pinto, and buckaroo. Thanks for your time.

Thanks for your time.